Artjaw.com is a digital collection of 50 first person stories from Philadelphia’s art community published between 2006 and 2013. Through the narratives of people who have been involved in its many different corners, Artjaw aimed to merge the everyday with the complex dynamics of the artworld. From artists to collectors, students, and curators, these individual stories peel back the curtain as much as they connect us to each other. The site is no longer live but scroll down for sample stories and sample audios. Get in touch if you want to read a story from one of the writers that is not posted here.

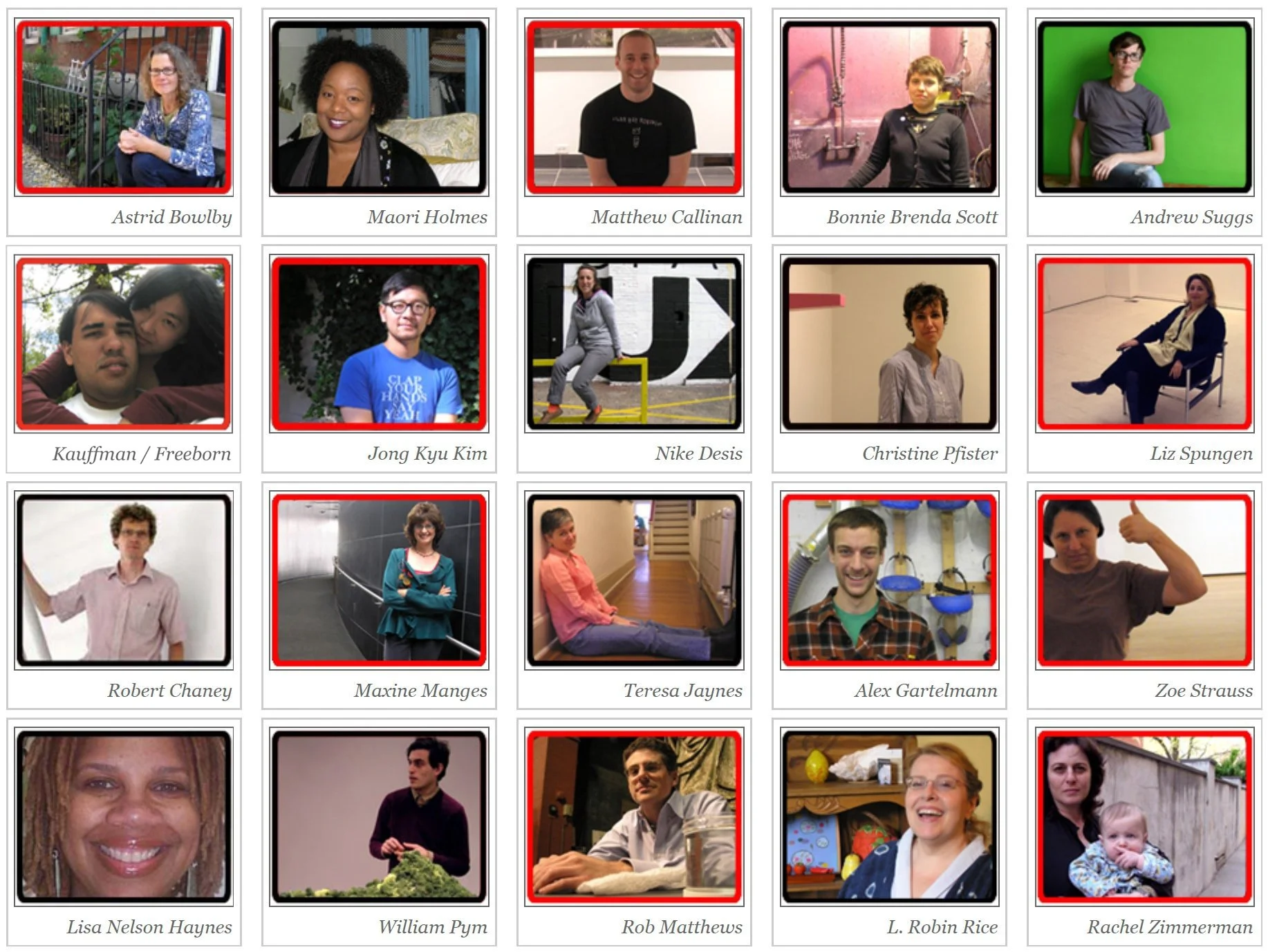

Above: Screenshot from the original website. Full list of contributors:

David Bond, Eoin Burke, Astrid Bowlby, Matthew Callinan, Robert Chaney, Bob Cozzolino, Julie Courtney, Nike Desis, Jim Dessicino, Fritz Dietel, Leah Douglas, Elizabeth Doering, Amy S Kauffman and John Freeborn, Alex Gartelmann, Lisa Nelson Haynes, Daniel Heyman, Maori Holmes, Aryon Hoselton, Jeanne Jaffe, Jong Kyu Kim, Stephanie Koenig, Shelley R. Langdale, Kent Latimer, Maxine Manges, Bernardo Margulis, Rob Matthews, Bridgette Mayer, Annette Monnier, John Ollman, Ashley Peel, Caitlin Perkins, William Pym, Christine Pfister, Jacqueline van Rhyn, L Robin Rice, Roberta Fallon and Libby Rosof, Bonnie Brenda Scott, Judith Schaechter, Matt Singer, Shelley Spector, Liz Spungen, Zoe Stauss, Andrew Suggs, Richard Torchia, Kate Ware, Nadine Bernard Westcott, Lewis Wexler, Rachel Zimmerman and Pensive Young Brunette (painting at the Philadelphia Museum Of Art)

Rob Matthews

Artjaw 2006

Artist, published while artist and Adjunct Instructor, University of Pennsylvania

I worked for the Philadelphia Museum of Art for five years. My job title was “Conservation Technician.” While the word “conservation” suggests that the job requires skills in preserving art, the word “technician” completely cancels that out. We had no lab or office. Instead we had a Rubbermaid cart loaded with cleaning supplies, a pager that kept us in contact with the main lab, and a couple of tins of Altoids mints. Fresh breath is expected from all PMA employees.

We worked in the public galleries. Most days were filled with mindless conversation with my three co-workers on our familiar path through the museum, dusting tabletops, washing glass, and hearing visitors make the same comment: “When you get finished here, you can come clean my house!”

99% of our job was dusting frames, furniture and sculpture. We also cleaned nasty fingerprints, nose prints, and various bodily fluids off the glass and Plexiglas cases. The other 1% of the job was large-scale, limited-skill jobs that the real conservators (the ones with degrees) didn’t have time to finish. In the past, that had included replacing rotten potatoes in Victor Grippo’s Analogía sculpture with not-so-rotten potatoes, cleaning the bird poop off of Rodin’s Gates of Hell, vacuuming tapestries, etc.

During one regular cleaning day, the pager started beeping. I took the elevator down seven stories to the underground tram that the museum has for its workers, and rode for approximately 25 minutes to the undisclosed location of the conservation lab.

In the lab I was given a jar of Plexi shavings, and three more jars with different clear liquids in them. Only one of the liquids was labeled. I was told to go to the Duchamp collection gallery and try to repair the graffiti that had been scratched into the surface of a window. Instructions for the materials were explained to me in about five seconds. It sounded like I was supposed to melt the Plexi shavings with one of the liquids and then paint the mixture onto where someone had scratched “BD” into the window.

“How much Plexi should I put into the liquid?” I asked.

“Just feel your way through it. It’ll be fine.”

The window in the Duchamp gallery is located four feet from the Bride Stripped Bare sculpture. It looked out to the fountain in the front of the museum and had quite a few initials scratched onto it.

I think I had a jar of acid to melt the Plexi, a jar of something to stop the acid, and a jar of something to clean the window, but once the lids came off, I didn’t know what anything was. I tried to paint the window with the liquid that melted the Plexi, but it started to drip. I took a paper towel and dabbed away the drip. It smeared. Let me be clear, the drip did not smear — the window smeared. I didn’t realize that the surface of the window had been compromised. Rather than leaving well enough alone, I took the paper towel and now did not dab, but instead wiped. What started out as “BD” turned first into a small melted section in the window and then into a 3” circle at eye-level in one of the most visited rooms in the PMA. Now I had left my mark at the museum.

I turned around to see if any visitors were there, but instead saw half of the contemporary curatorial staff. I looked at them; my mouth dropped open, then I looked back at the window and said, “Looks like I made it worse.”

I heard a long sigh, and saw a look that seemed to say, “We knew you couldn’t do this, but we’re still disappointed”.

One said, “Well, we’ve wanted to replace that window for a long time anyway.” They walked off. I scraped my jars together and headed back to the lab.

“So how did it go?”

“I made it worse.”

“Oh, well.”

Within the week, my mistake was forgotten by all but me. The window was replaced a few months later. My normal routine resumed: walking the regular path through the museum, scraping human fluids off the glass, and getting videotaped cleaning like an animal at the zoo. The heckling continued.

“When you get finished here, you can come clean my house!”

Followed by someone cackling, “Oh! You’re a riot!”

Maori Karmael Holmes

Artjaw 2013

Artist, published while Associate Director of the Leeway Foundation

In 2005, I was encouraged to apply for a grant by an associate who worked at the Leeway Foundation. I was fortunate enough to receive two grants and one award, which encouraged me to keep on my path as an artist. I’d only recently received my MFA and was beginning to define my practice. It was the first grant I’d ever applied for or received. I began to apply for other grants. Some I got, some I didn’t. But receiving that first award, gave me the confidence to try.

I was later approached by the foundation to produce a special event. I had previously worked in art administration. That producing job turned into a consultancy, and then came the offer of a full-time position as communications director. In the summer of 2011 I became the associate director.

The duality of my life–as both arts administrator and artist–is complicated. On one hand, it allows me to witness directly the overwhelming joy and gratitude that artists feel when they are awarded a grant. We often hear that being awarded validates their work and lets them know they are “seen”. Over the years, several grantees and awardees have shared that the act of applying for funding was a last-ditch effort to make a career out of doing what they love.

On the other hand, some folks apply, crossing all their ‘t’s’ and dotting their ‘i’s’ and still don’t get funding, even when (I think) they’re deserving. When this happens – and it happens quite a bit – it is heartbreaking. One artist whose work I thought was outstanding applied for the same award three years in a row, and was rejected by three different panels. The artist took each previous panel’s advice and improved their application each time. As a former grantee, I know exactly what goes into the application process; the hours spent agonizing over the perfect wording to best describe your craft and purpose. But this artist never received the grant. After the third attempt, they didn’t apply again. My heart sunk. Our submission process is an emotional one that requires the artist to describe intimate details of their lives. To not want to go through that for a fourth time – after it not being enough each time before – is understandable.

Those of us on the staff at Leeway have no input in the decision-making—it is up to an independent panel of peer artists and cultural workers. This is a great thing because it enables us to assist applicants with presenting themselves in the best light and in many ways protects our relationships in the greater arts community.

I’ve sat in on more than twenty panels since being on staff. It is an arduous process, which involves a group of 3 to 5 peer artists and cultural workers who receive applications in advance and then spend either one or two days (depending on the funding program) evaluating applications by reading them thoroughly and then come to consensus on which artists should be awarded. The panelists are supplied with the foundation’s guiding principles on it’s mission of art for social change and asked to do the very hard work of saying “no”—which none of them ever wants to do.

We consider ourselves “kinder and gentler” than most. We call folks when they are missing elements from their applications and work with people who are novice users of certain kinds of technology. We are often the first to give an emerging artist funding. We allow folks a lot of leeway, if you will, because we know that what they’re doing as artists and activists is important, not only to them, but to their communities.

This is where trusting the process comes in. Though I cannot help but to be emotionally involved with some of the work of the artists that we fund, I also understand that the panelists we choose ultimately have the best interest of the foundation and its applicants at heart.

There is often a mystification of philanthropy, when in reality, it’s just people making decisions—people with their own logic for what does and doesn’t work. I have applied for (and received) other individual grants since my early days with Leeway and I always remind myself of this fact when I get rejected. As I work to pick myself up and dust off my expectations, I relish the fact that a) I can apply again, b) some other panel will be interested in my work, and c) when I sing Jermaine Jackson’s 1989 single “Don’t Take It Personal” (sic), it always makes me feel better.

Written with assistance from Julie Zeglen

Annette Monnier

Artjaw 2007

Artist and writer, published while co-founder and curator at Practice Gallery

To be totally fair, this story is only one-sixth mine. The other five-sixths are split equally between Carrie Collins, Gerik Forston, Jamie Dillon, Elsa Shadley and Nick Paparone. Together we created a gallery on the third floor of an industrial warehouse just north of Chinatown in Philadelphia. We painted the floor black and called the gallery Black Floor. We also lived and worked in the space for three years.

We were all well-behaved kids. We had jobs, tried to be sort of clean, and organized our messes. Mostly we voted on decisions and didn’t really want to crash the state. We would work 9-5, then have a beer and work some more. There were no crazy orgies or drugs. This isn’t weird until you took a look at how we were living. There was no hot water for the shower; we had a camp stove to cook on and dead mice at our feet. We slept in a circle, like we were a pack of wolves, underneath a buzzing fluorescent light that we couldn’t turn off. Then Carrie pitched a tent in the middle of our disorganized pile of belongings.

Each of us had the option to live normally. We weren’t victims, except of our own ambitious dreams, and those dreams were to build an art gallery and launch our own microcosm of the art world at large. It wasn’t easy and we were serious. The art world we were building wasn’t going to be glamorous. It was going to work all day, only relaxing when it drank cheap beer at night. It was going to yell at its housemates and stew in its anger for days. It was going to be a perfect fit for the City of Philadelphia.

I won’t say that building a white rectangle with a black floor was easy, especially for people with little to no building experience. Drywall is a bitch. It’s expensive if you’re broke, and it didn’t really fit into the elevator. It is also very heavy. I remember all of that, but still it just seemed like the gallery appeared one day and then, suddenly, life had a whole different set of rules. There was now an island of order within our disordered world. You could see it from the kitchen, look at it while you brushed your teeth, but you didn’t really step into it. It was better then you.

For two and a half years, the six of us hosted art exhibitions every month. The artists came in and did what they were planning to do (mostly). Once everything was going, it felt like we had nothing to do with the production of it, like the gallery was a river and it would be tougher to dam it up to stop the flow. Running the gallery was both easy and hard. At some point an overwhelming and inexplicable lethargy injected itself upon us like a seventh roommate.

Black Floor was an entity that had its own momentum and its own sense of timing. As one person in a group of six I could feel the inevitable taking over, even though I really didn’t want it to. The choice was simple: we could end what we started, or we could become a bad reflection of ourselves. We were done with Black Floor before the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia invited us to be a part of a show called Locally Localized Gravity. This afforded us the perfect ending.

During Locally Localized Gravity we enjoyed the perfect Utopia of being part of a project that had a clear, solid ending, and it was then that I felt the closest thing to regret I had ever felt about our decision to disbar. My roommates were beautiful, perfect reatures and all of their flaws were charming. Drunkenly, sometimes with tears involved, I talked to them about keeping it going. Soberly, I knew it was over. It’s better to pull the Band-Aid off quickly then to heed the siren call of the past.